The Covid-19 recovery continues. Unemployment keeps falling, employment keeps rising and vacancies have hit record highs. Wages are actually rising for employees within hospitality, food processing, warehousing and lorry driving. This applies even for one of the groups hit hardest by the pandemic: young people (aged 16 to 24).

But we are worried that job recovery for young people will also be the hardest fought. Why?

- Because there may be permanently fewer jobs in industries, like hospitality, that traditionally employ young people.

- Many new jobs will be insecure.

Post-secondary school education is not providing young people with the appropriate skills for the future of work.

As a consequence, there is a risk of persistent higher unemployment and lower wages for young people in the long-run, with knock-on effects on the rate of labour exploitation.

Young people’s jobs have disappeared

We know that Covid-19 disproportionately impacted young people due to related restrictions affecting service sector jobs. The recovery is no different. Around 200,000 (2.5%) fewer young people between July – September 2021 were in employment than before the pandemic. Compare that to only 1% fewer 25+ year olds.

Even in hospitality, which is seeing record vacancies, the number of overall workforce jobs (vacancies + filled positions) is well below pre-pandemic levels.

And there is good reason to think that some jobs won’t ever come back. The GLA Coronavirus Mobility Report shows that retail and recreation footfall in London remains around 10% below pre-pandemic levels. Persistent working from home (highlighted in the same report) saw between 10 – 48% fewer Londoners travelling into the workplace on any given day in October 2021. Internet sales (i.e. online shopping) as a proportion of all retail sales now is much higher in the UK than it would have been if it had followed its pre-pandemic trend. These types of pressures have seen cities like London, where young people concentrate, experience the highest unemployment.

We also do not know what the future holds. Reimposed Covid restrictions seem more likely with the rise in cases as we head into winter.

Insecure work is back on the rise

And even if our concern about a loss of jobs is overblown, there is another risk that the jobs available will be more insecure (i.e. the earnings or the job itself are not predictable or guaranteed).

ONS employment data shows us that in the period July – September 2021, 6% were temporary employees, up from 5.1% in the same period prior to Covid. That’s a 17% rise!

Insecure work isn’t necessarily a bad thing – some people appreciate the flexibility. But the fact that 30% of people working temporary jobs are only doing so because they cannot find permanent positions suggests that many would prefer more stable employment. Young people in insecure work report greater mental health issues too.

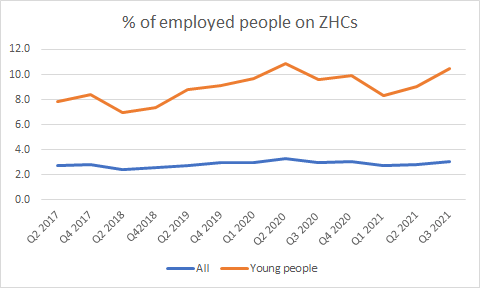

Much of the rise in insecure work is driven by a large increase in fixed period contracts, but casual work and agency temping is back on the rise over the summer of freedom, having actually fallen in the midst of the pandemic (see ONS data). The proportion of young employed people on a zero hour contract (ZHC) peaked in Q2 2020 in the midst of the pandemic, fell a little, but now is back on the rise. As you can see in the figure below, young people are much more likely to be on ZHCs than the rest of the population.

We’ll need to wait to see whether this trend in insecure work is persistent. But if the recovery from the Global Financial Crisis is anything to go by, then insecure work is likely to become more prevalent and will affect young people most prominently (see Resolution Foundation research from 2019).

Education isn’t fit for purpose

During the pandemic, there was a sharp rise in economic inactivity. This is where people of working age are not looking for a job at all (as opposed to the unemployed who are actively seeking work). This increase was particularly stark for young people and there are still 3% more young people in this category than before the pandemic.

This has been primarily driven by young people returning to education.

This sounds sensible. Young people who lost their jobs in hospitality and accommodation decided to up-skill to enable a career change, or just wanted something to do.

Unfortunately, it is unlikely that the skills they’ve obtained will be transferrable to the actual jobs available. Acute post-Brexit related staff shortages are in lower skill entry areas like food processing or warehousing, or require very specialist skills like a heavy goods vehicle licence. And unless pandemic induced study is wildly divergent from recent studying trends in the UK, then it will not have combatted the long-term UK skill deficiencies in STEM, nor the general rise in skill-shortage vacancies since 2011 (i.e. those vacancies proving hard to fill due to difficulties in finding applicants with appropriate skills, qualifications or experience).

For example, construction, manufacturing and primary industry sectors experience the highest proportion of skill-shortage vacancies compared with overall vacancies. Mostly they need skilled tradespeople. But while bachelor degree growth has been strong in the UK (reaching a record high in 2019/20), uptake of higher technical qualifications that might fill these shortages has languished and even fallen in absolute terms since the 2000s. A longitudinal study of outcomes for individuals who took GCSE’s in 2004/05 found that the number of students who achieve higher technical qualifications as their highest qualification is very small (4%) compared to the number who only reach A-levels (26%) or finish undergraduate degrees (26%).

Labour shortages in the short term may be leading to wage rises in those sectors struggling to fill vacancies. But in the longer term, if the market for education fails to match supply of skills with demand, then this will put downward pressure on wage growth because workers will be less productive and unable to negotiate better pay at the outset.

How is this all related to labour exploitation?

Well, if young people have the wrong skills in a labour market with fewer jobs in traditionally young-people-employing sectors (like hospitality), then they are at greater risk of persistently high unemployment. Unemployment when young is distressing in the short term and well-established to leave ‘scars’ affecting pay and wellbeing in the long-term. For those that do get a job, it is more likely to be insecure and provide little in terms of pay progression. The Health Foundation has written about the negative impact unemployment has on mental health, and we know that insecure work is not much better on that front.

FLEX identifies factors such as insecure work, mental health issues, debts and low pay as contributing to an individual’s vulnerability to labour exploitation. Our fear is that there is a large population of people who will be increasingly vulnerable to exploitation over the coming years.

What should be done?

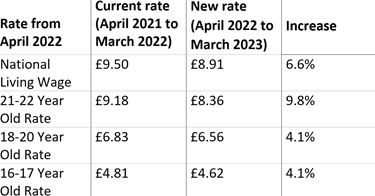

On the issue of pay, the Autumn 2021 Budget and Spending Review did accept the Low Pay Commission’s recommendation to raise the minimum wage to £9.50. That is welcome, especially as the higher rate will cover all people over the age of 23. But the rate for 16-17 and 18-20 year olds will need to be hiked up again in late 2022 to ensure their rise is protected from 4+% inflation (Bank of England forecast).

To help young people develop new skills and get into new sectors the Government should

- Indefinitely extend the Kickstart Scheme which is attempting to provide work placements to 16-24 year olds who are at risk of long term unemployment.

- Cover set-up costs for level 4-5 apprenticeships, as occurs for work placements in the Kickstart Scheme, and remove any co-investment requirement for non-apprenticeship levy payers.

- Introduce a skills tax credit for employers who invest in training for workers.

To address the rise in and vulnerability associated with insecure work, the Government should

- Fulfil its promise to give workers on a ZHC the right to request a more stable contract

- Provide workers on a ZHC with the right to reasonable notice of shifts and shift cancellations

- Adapt piece rates legislation to govern how app-based workers are paid the National Minimum Wage

- Give agency workers a right to request a direct contract with the hirer

Without policy change, we fear that the future for young people is less prosperous and more open to labour exploitation.

By George Ritchie