Poverty. We’d prefer to think that it doesn’t exist in the UK, but it plainly does.

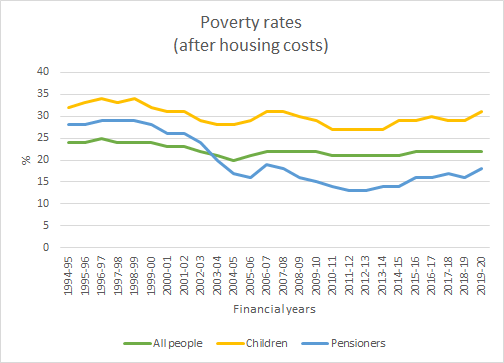

And we haven’t made much recent progress towards eradicating it. The rate of relative poverty in 2019/20 was scarcely different to that before the Global Financial Crisis, at around 22%.

Which is equivalent to 14.5 million people.

Pre-pandemic poverty

On the graph below, sourced from data provided by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and collected by DWP, you can see how the rate of relative poverty for the entire population (the green line) was closer to 25% in the mid-90s, came down significantly in the period to 2004/05, but subsequently rose to 22% and stayed there until the start of the pandemic.

There are a number of reasons for this disheartening pre-pandemic track record:

- Earnings growth (i.e. hourly wages and salaries) has been weak – so on average people aren’t getting paid much more than they were a decade ago.

- And while employment has been strong (for example, the employment rate reached its highest point ever in 2019), much of the new work has been insecure (non-permanent, not guaranteed work with too few hours and too low pay) and the number of working people in poverty has been rising since 2011/12.

- Simultaneously, working-age benefit entitlements were cut and frozen in the years of austerity, so benefits did not even keep up with the meagre income growth.

- And private and social housing rents have increased for those on low incomes since 2000/01.

This combination of tough welfare policy and difficult employment and housing conditions ultimately kept many UK households in relative poverty in the decade leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Post-pandemic poverty

The situation has only gotten worse for those on very low incomes:

- Covid-19 has pushed more people into unemployment (4.5% in August 2021 compared to 3.9% in the same period of 2019) and the end of furlough is expected to have pushed more people into joblessness.

- The Covid-19 sparked Universal Credit uplift of £20 per week is now gone. This affects 5.8 million people (almost half of whom are employed but not earning enough to get by).

- The energy price cap rise will see a 12% increase in energy prices as we head into winter.

- Labour shortages and supply chain chaos has pushed up the price of basics like fuel and food and prices are generally projected to rise further.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation expects that 500,000 extra people have been pulled into poverty due to the end of furlough and the Universal Credit uplift alone. The Resolution Foundation projects 1.2 million people to enter poverty in 2021/22. (Click here to view these findings and more statistics on poverty in the UK).

Regardless of the exact figure, the outlook for many, many people in Britain is looking bleak.

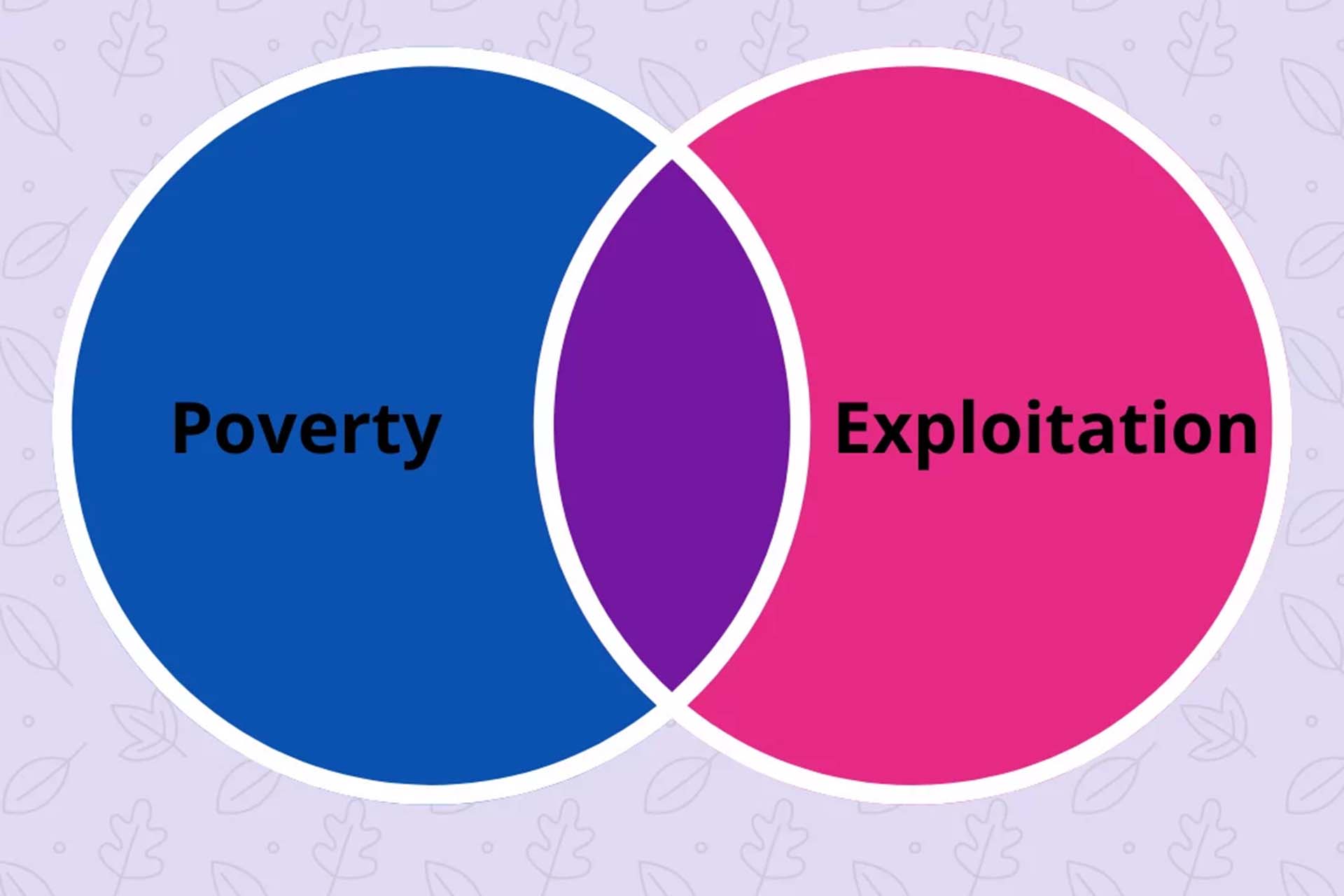

What does this have to do with exploitation?

Poverty in the household contributes to stress, food insecurity and domestic abuse. And we are worried that as more families, children and pensioners enter poverty, a greater number will also become the victims of criminal, labour and sexual exploitation.

The ILO has pulled together much research on the link between poverty and exploitation and found that wherever someone is from, whatever their situation is, poor households find it hardest “to deal with income shocks, particularly those that push households below the food poverty line.” And when this does happen and there are no safety nets to protect them, people become more desperate to borrow from unscrupulous lenders and take any job even if it’s exploitative. That is why we are talking about poverty.

What next?

This time presents a great opportunity for the Government to tackle poverty and exploitation head on. We recommend the following to help ensure more people stay out of exploitation:

- raise financial support for those without work and the very low paid and crack down on non-compliance with labour law

- enable and fund statutory bodies, including labour inspectorates, to better identity and support victims of exploitation.

To prevent exploitation the Government must aim to eradicate its root causes, including poverty.

By George Ritchie